The secondary 2 edition of the good old geography textbooks we have used some 30 years ago touches on various topics, such as the environment, interaction, growth and change, hierarchy, unity and diversity.

Like the other editions, there are many maps, illustrations and photos in this textbook that can bring us back to feel how the life was in Singapore in the early eighties.

A set of rattan furniture with a 20″ CRT television. That was perhaps the standard design of a living room for a middle-income family.

Haze was not uncommon back then. Records show that Singapore was affected by polluted air, although not on a yearly basis, since the seventies. The smokey days were mostly caused by massive forest fires at Sumatra and East Kalimantan.

A class of some 30 students. A stern-looking teacher standing in front of a large blackboard with white chalks. That was the typical classroom scene of the eighties we were once familiar of.

Various kinds of transport, private or public, of Singapore in the early eighties were displayed in the photo above. One glaring difference as compared to the present day; there was no MRT yet.

The license plate of the private car shows “EM”, which belongs to the E-series. The E-series (EA to EZ) commenced in 1972 and ended in 1984, when it was replaced by the SB-series (and subsequently SC-, SD-, SF-, SG-, SJ- and SK-series).

Notice the phone number on the van’s advertisement which had seven digits. Prior to 1985, fixed line numbers in Singapore existed in five or six digits. As the demand for new phone numbers rose in the early eighties, the seven-digit format was introduced.

The rise of handphones in the nineties saw mobile numbers adopting the new eight-digit format. In 1995, the digit “9” was added in front of the mobile numbers. “6” was later added as the first digit of the fixed line numbers. By 2002, all phone numbers in Singapore were standardised to the eight-digit format.

The prominent overhead bridge used to span across Collyer Quay, connecting together Aerial Plaza and the Singapore Rubber House and Winchester House on the other side. A popular place with tourists and foreign sailors for bargain hunting, the Change Alley offered a wide range of goods such as watches, bags, shoes and clothing. Numerous money-changers, both legal and illegal, also ply their trades here.

In 1989, the old Change Alley was shut down when the Singapore Rubber House and Winchester House were demolished. Today, Change Alley, and the overhead bridge, is a modern mall with a mixture of retail shops and restaurants.

Plans to develop Ang Mo Kio as a self-sufficient new town started as early as 1973. It was the seventh housing estate to be developed by the Housing and Development Board (HDB). By the late seventies, the six neighbourhoods of Ang Mo Kio was generally completed with streets, markets, schools, community centres and places of worship.

The Singapore River was then filled with twakows and tongkangs (traditional light good-carrying vessels). The cleaning up of the Singapore River began in 1977, and took ten years for the river to be freed of pollution, garbage and old wooden bumboats.

In 1984, the first “Swim Across Singapore River” was held successfully, followed by a series of water activities such as the “Singapore River Regatta” (1985), “River Carnival” (1986), and the “Dragon Boat Race” (1987) that demonstrated the new-found cleanliness of the river.

Originally known as the Oranje Building, the Victoria-styled Stamford House was designed and constructed in 1904 by prominent architect Regent Alfred John Bidwell (1869-1918), who also built the Raffles Hotel and Goodwood Park Hotel.

In 1984, the Stamford House was acquired for conservation by the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA). It was given a restoration at a cost of $13 million in the mid-nineties.

Three features in the above photo that had already vanished in today’s context. The first was the road between the two rows of shophouses. Emerald Hill Road was then linked to the main Orchard Road. In August 1985, Emerald Hill Road was designated by URA as a conservation area with its Peranakan buildings preserved. Part of the road was shut down and redeveloped into the covered walkways of the new Peranakan Place.

With the road closed, the overhead gantry of the Area Licensing Scheme (ALS) at Emerald Hill Road was removed. ALS was started in mid-1975 to control the traffic entering the downtown area. It was later replaced by the Electronic Road Pricing (ERP) scheme. The third was the Specialist Shopping Centre, built in the early seventies and operated for more than three decades before it was demolished in 2008. During its heydays, it housed John Little, the oldest department store in Singapore, and the 392-room Hotel Phoenix.

The General Post Office, in 1928, became the anchor tenant of the Fullerton Building, just two weeks after its official opening. From there, it operated for almost seven decades, before the post office headquarters, fondly known as “GPO” by Singaporeans, was relocated to the new Singapore Post Office building at Eunos Road in the late nineties. The Fullerton Building was then acquired by Sino Land for $400 million, which converted it into a boutique hotel named The Fullerton Hotel in 2001.

The double-storey colonial building of Tanglin Post Office, on the other hand, was also a prominent landmark, having existed at Tanglin Road since the early 20th century. It was eventually demolished in 2008.

Hong Kong Street, located between New Bridge Road and South Bridge Road, used to have many trading houses and wholesalers doing businesses in the shophouses. Today, the street is better known for the bars, clubs and boutique hotels.

Typical old provision shops, like the Tan Seng Thye Provision Shop at Alexandra Road, used to be a common sight at the HDB neigbourhoods. Selling everything from dried food and instant noodles to cigarettes and batteries, there were as many as 1,200 provision shop in Singapore in the seventies. Since then, their number has been dwindling due to stiff competition from the minimarts, convenience stores and supermarkets.

The decision to introduce rail-based MRT system was finalised in 1982, after a decade of feasibility studies. Tunnel burrowing and stations’ construction began shortly after. The first MRT stations were opened in late 1987 between Yio Chu Kang and Toa Payoh of the North-South (NS) Line.

The new MRT system was a great success, both in technical achievement and public opinion. Just three weeks after the opening of the NS Line, the MRT recorded its first millionth ridership.

Singapore’s population in the early eighties stood at around 2.5 million. After a series of birth controlling services and campaigns by the Family Planning and Population Board (1966-1986), Singapore’s total fertility rate (TFR) dropped below 2.1 in 1977. It was the first time the TFR dropped below the replacement rate since independence.

By 1984, policies were introduced to get singles hitched. Three years later, the “Have Three or More if You Can Afford it” campaign was launched in anticipation that the birth rate would recover by 1995. It never did.

Back to A Flashback to Singapore 1982 Through Old Geography Textbooks (Part 1).

Published: 28 September 2014

It was the end of road for the Toyota Crown taxis in Singapore, when its last batch officially walked into history in September 2014. Debuted since 1982, the Toyota Crown taxis were once one of the most common taxi-cabs on the Singapore roads in the nineties and 2000s, along with the models of Toyota Corona and Nissan Cedric.

The last batch of Toyota Corona taxis was scrapped in 2006. Today, the new taxis come in almost 30 different types of models, ranging from Toyota (Axio, Camry, Wish, Allion, Prius) and Honda (Fit, Airwave, Partner, Fielder, Stream) to Hyundai (Sonata, i30, Avante), Kia (Magentis, Optima, Carnival) and Chevrolet (Epica).

Other than the models, how have Singapore’s taxi-cabs evolved in the past 100 years?

1920s – Early Taxi-cabs in Singapore

Prior to the 1920s, rickshaws were widely used in Singapore. Imported from Japan since 1880, the hand-drawn taxi-cabs provided a major form of public transport to both the upper and lower class. Although rickshaws were eventually banned in 1947, the Municipal Commissioners were already aiming to replace the rickshaws with small taxis in the 1920s.

Engine-driven type of taxi-cabs started to appear in 1920, when Ford touring cars, painted in light yellow with black fenders, became available at Raffles Place, charging passengers at a rate of 40 cents a mile with an additional 10 cents for every quarter mile. The first true taxi-cab, designed and fitted with a Ford chassis, an economic carburetor and ample seating accommodation, was brought into Singapore only nine years later.

The Borneo Motors Limited imported the taximeter in 1930 as an experimental device for taxis in Singapore. The meter had been used in other countries such as Rangoon and Calcutta for many years. Fitted at the running board of the taxi, the driver would pull down the “For Hire” flag whenever a passenger boarded the vehicle, and the mechanism in the meter would start registering the fare. The taximeters, however, did not become a compulsory device for taxis until years after the Second World War.

1930s – Rise of the Yellow Top Taxis

The first yellow top taxis were brought into Singapore in 1933 by the Wearne Brothers, founded in 1906 and later became the sole agent of the Ford cars in the Straits Settlements, to primarily serve in the city area. The response was generally positive; a year later, Wearne Brothers established a subsidiary named General Transport Company to launch taxi services in other Malayan cities such as Malacca, Penang and Kuala Lumpur.

1940s – The First London-type Taxi

Just after the end of the Second World War, the Singapore Hire Car Association (SHCA) and Singapore Taxi Transport Association (STTA) were formed with the approval of the Registrar of Vehicles to protect the interests of their members plying the trade of taxi drivers. The associations would also step in to provide legal services to the drivers in times of conflicts.

In 1946, the official basis of charges for taxis in Singapore was set at 30-cents-a-mile by the Road Transport Department.

An Austin 1949 model arrived in Singapore in November 1949 as the colony’s first ever London-type taxi, causing quite a stir as pedestrians and passengers gazed at the vehicle with interest. Designed with a capacity to carry five passengers, the new taxi, however, was out of reach for most drivers due to its high cost of $7,000.

1950s – Taximeters A Must

In order to provide a fairer service to the public, taximeters were finally introduced on a wider scale in Singapore by the City Council in the early fifties. The new scheme was not well-received, as the taxi drivers felt that it was a practice for passengers to bargain and pay fares below the authorised rates, and the introduction of taxi meters would disrupt their business. Nevertheless, the Singapore Taxi-Owners Co-operative Motor Garage and Stores Society Limited, a major taxi company in Singapore, became one of the first taxi companies to adopt the meters. By the end of 1953, all taxis in Singapore were required to install the taximeters.

Other new measures also generated negative responses. In 1954, a plan to install radio telephones in the 1,500 taxis in Singapore was met with protests and objections due to the high installation fees that cost as much as $800.

In 1957, the City Council wanted to add more taxis on the road, and this, too, was met with objections as it would increase the competition and reduce the taxi drivers’ and owners’ earnings. Moreover, pirate taxis were running rampant in Singapore, taking away a large share of the legal drivers’ business. The same year also saw the restriction of taxis travelling freely between Singapore and the Federation of Malaya. Prior to 1957, vehicles could travel in both territories without restriction.

The number of taxis in Singapore, by the end of the fifties, had ballooned to 11,500. Most of them were under the Singapore Taxi Transport Association, Singapore Hire Car Association, Singapore Taxi Drivers’ Union and Singapore Hock Poh Sang Taxi Drivers’ Union. The increasing number of taxis indirectly led to a higher number of accidents on the road, averaging 2,000 per month. While the accidents were not entirely due to the taxi drivers, their eagerness to pick up passengers and road manners often put them in unfavourable situations with the Traffic Police.

1960s – Fighting the Pirate Taxis

By the sixties, there were more than 36,000 licensed taxi drivers in Singapore, where 90% of them belonged to three major taxi companies in the Singapore Taxi-Owners Co-operative Motor Garage and Stores Society Limited, STTA and Sharikat Sir Kemajuan. STTA is the only one still existing today, providing coverage for the private taxi owners identified by their yellow top vehicles.

Pirate taxis continued to be a source of issues in the sixties. Anyone could register their private cars as taxis, and used them to ferry passengers at arbitrary rates. Some, known as “Ali Baba”, were controlled by rogue operators that owned fleets of poorly-maintained vehicles at their territories. Taxi licenses were often traded by them at exorbitant values. In the mid-sixties, as many as 4,000 pirate taxis were running on the roads everyday.

1970s – Radio Taxi Services Launched

In 1970, the NTUC Workers’ Co-operative Commonwealth for Transport was established with a fleet of 1,000 taxis. It would later become NTUC-Comfort, the largest player in the local taxi-cab industry for decades. Taxi licenses became non-transferable in 1973; the new taxi licenses were only issued to NTUC-Comfort.

The total number of taxis in Singapore in 1970 numbered about 10,500, but most of them were still pirate taxis. It led to the introduction of diesel tax, one of several measures by the government to wipe out pirate taxis. Facing uncertainty and unemployment, many pirate taxi drivers decide to switch to licensed taxis with NTUC-Comfort, or became bus drivers or conductors. By July 1971, pirate taxis in Singapore were officially “eradicated”.

The radio taxi service had been present since the fifties, but it was never popular with the public due to its unreliability. The pirate taxis also played a part then, as the commuters could easily booked one instead of calling the legitimate taxis.

In 1976, the radio taxi service started by the Singapore Taxi Owners and Drivers Co-operative Store Society, which had 190 taxis under its charge, finally proved to be a success with the public with easy-to-memorise dial-in numbers such as 363636 and 363333. In just the first eight months of service, the organisation had received 50,000 booking calls.

Soon, other taxi companies also followed suit; the Singapore Taxi Drivers Association started their radio taxi service a year later, and NTUC-Comfort launched theirs in 1979.

By the late eighties, there was more than a dozen private radiophone taxi organisations spread all over Singapore in Singapore. Most had ceased operations by today, such as the Beach Road Radio Taxi Service (at Jalan Selaseh), Chip Bee Radio Taxi Service (at Upper Bukit Timah) and Upper Thomson Radio Taxi Service (at the long-demolished Lake View Shopping Centre).

Only a handful still exists till this day. They are the Sembawang Hill Estate Taxi Service (at Jalan Leban), Boon Lay Garden Radio Taxi Service (at Boon Lay Place) and Singapore Radio Taxi Service (at Ulu Pandan Road).

1980s – Expanding Market

Air-conditioned taxis were introduced in 1977, a move welcomed by the public. More measures for taxis were rolled out in the eighties. In 1982, radios were allowed to be installed in the taxis. In the same year, front-seat seat belts were made compulsory. In the early eighties, NTUC-Comfort made a step ahead of others by changing all their taxis’ mechanical taximeters to electronics ones. By 1984, all taxis in Singapore were required to be fitted with the electronic meters.

There were 11,668 taxis running on Singapore roads by 1985, shared by the Singapore Commuters, NTUC-Comfort, Singapore Airport Bus Services (SABS) and SBS Taxi. NTUC-Comfort continued to own the largest taxi fleet, with almost 6,300 cars, whereas there were only 300 taxis under SABS.

SBS Taxi, a new player joining the market just two years earlier, launched their Toyota Corona taxis in white and red colours, the same signature colours used for their SBS buses.

1990s – The Big Merger

In 1995, CityCab was formed by the merging of SABS, SBS Taxi and Singapore Commuters. A year later, it became the first taxi company in Singapore to launch a luxurious fleet of Mercedes E300 taxis. A 7-seater named MaxiCab was also introduced by CityCab in the late nineties.

Today, there are six taxi companies in Singapore, namely Comfort, CityCab, SMRT, TransCab, Premier and Prime. The green SMART Cab, established in 1991, was the latest taxi operator to exit the industry after failing to meet the Quality of Service requirement set by the Land Transport Authority (LTA) in 2013.

Other than the six taxi operators, there are around 500 yellow top taxis in Singapore driven by their individual owners. The licenses of these yellow top taxis allow their owners to drive the vehicles until the age of 73, which means the yellow top taxis, running on the roads since the 1930s, will probably vanish in the next decade or so.

Published: 02 October 2014

Keppel Hill, off Telok Blangah Road, has become a new place of exploration in Singapore ever since the newspapers published the rediscovery of an abandoned reservoir by the National Heritage Board.

The forgotten reservoir, reported to be dated as early as 1905, had appeared in the early maps. But by the fifties, it had vanished from the maps and its location was not officially marked for sixty years.

The 2m-deep reservoir is not easily visible although it is located at a short distance away from Keppel Hill Road. Nature has reclaimed it over the decades, as the overgrown vegetation shields it from public attention. The stagnant pool of water is also filled with dry leaves and twigs.

Remnants of the reservoir still exist today, such as concrete steps, an old diving board and a bathing area. There are also new pipes and pumps, appearing to be in fine working conditions, linking to the reservoir that is only about one-third of an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

Prior to the fifties, the reservoir was marked as a private property and, later, a swimming pool. In March 1948, the newspapers reported that a 17-year-old teen was drowned when he went swimming in the reservoir with two of his friends.

The abandoned reservoir is situated near to No. 11 Keppel Hill, one of the grandest houses in the vicinity. There is also a mysterious tombstone of a Japanese general located behind the reservoir.

Published: 11 October 2014

Fountains were originally used to provide drinking water for the public, especially in the early Western civilisations. The ancient Romans were among the first to use fountains as decorative ornaments for their cities. During the 7th century, the Arabs built the famous Islamic gardens with elaborated use of fountains as part of their landscapes.

In Singapore, the first public drinking fountain appeared in 1864 through the donation by English merchant John Gemmill. After Singapore’s independence, fountains were popularly used to beautify new towns, roundabouts and landmarks.

How many iconic fountains in Singapore do you remember? (The list below is not in any alphabetical or chronological order)

Fountain of Wealth (1995-Present)

Constructed in 1995, the Fountain of Wealth at Suntec City stands 13.8m tall and is mainly made of silicon bronze. Listed by the Guinness Book of Records as the largest fountain in the world in 1998, the iconic structure represents the unity and harmony among Singapore’s various races, with its design inspired by Hindu mandala.

There is also fengshui element incorporated into the fountain’s design and location. The five tower blocks symbolise the “thumb” and “fingers”, and the fountain is situated at the “palm” where the wealth, represented by the inflowing water, pours in.

Sentosa Musical Fountain (1982-2007)

It took a total of 10 years to build the iconic Sentosa Musical Fountain. Construction began in 1972, the same year Sentosa was officially slated for development. Costing as much as $3.2 million, the star attraction of Sentosa would be located at the northwestern part of the island named Imbiah Bay.

The Musical Fountain was officially opened in June 1982, and was at one time the largest outdoor fountain in Asia. Able to accommodate 5,000 people, the fountain became the popular venue for a series of shows, events and displays. In 1996, the gala dinner of the World Trade Organisation’s Ministerial Conference was held at the Musical Fountain.

For its 25 years of history, the fountain was regularly renovated and restored, with artificial cliffs, colonnades and waterfalls added. In 1996, the gigantic 37m-tall Merlion statue was built, and the laser light beams shooting from its eyes became part of the Musical Fountain’s shows.

Together with the Musical Fountain, the Fountain Gardens promenade was another attraction of the island. Opened in 1989, it was located between the former Ferry Terminal and the Merlion statue, and consisted of many features such as dragon sculptures and European-style gardens that were inspired by French and Italian Renaissance designs.

After years of decline in visitorship, the Musical Fountain, Fountain Gardens and Ferry Terminal were shut down in March 2007 and subsequently demolished. They were later replaced by the Resorts World Sentosa.

Kallang Park Fountain (1959-1980s)

The 15m-tall Kallang Park Fountain was erected by the Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce as a gift to the City Council of Singapore. Designed by Messrs H. Sena, the fountain was an eye-catching attraction when the $50-million Singapore Constitution Exposition was held in early 1959 at the disused runway of the former Kallang Airport.

In the 1960s, the Kallang Park, with its spacious premises, playground and sport facilities, was a popular venue among the locals. It was situated at a short distance away from Dakota Crescent and its iconic seven-storey red-brick SIT flats that were mostly built in 1958.

Raffles Place Park Fountain (1960s-1980s)

The Raffles Place Park was a decorative garden on top of the underground carpark where the Raffles Place MRT Station is today. The fountain, along with flower beds, lawns and a giant Seiko-sponsored clock filled up the garden that was extremely popular with the public in the sixties and seventies.

The underground carpark, however, had to give way to the construction of the new MRT station in the eighties, and together with it, the demolition of the garden and its ornamental fountain.

National Theatre Fountain (1963-1984)

The National Theatre, fondly remembered by the older generations of Singaporeans, was an iconic landmark standing on the slope of Fort Canning Park along River Valley Road. Also known as the “People’s Theatre”, its construction was made possible by the generous donations from people from all walks of life.

The theatre’s distinctive design of five-pointed facade and fountain represented the stars and crescent of Singapore’s national flag. It was the brainchild of local architect Alfred Wong, whose firm won the design competition to build Singapore’s first national theatre.

Opened in 1963, the National Theatre was the selected venue of many important events and performances. Its usage, however, had gradually declined by the early eighties. Its damaged cantilever roof, lack of air-conditioning facility and the plan to build the Central Expressway’s (CTE) underground tunnel close to its site led to the government’s decision to shut down the National Theatre in 1984. It was subsequently demolished two years later.

Tan Kim Seng Fountain (1882-Present)

Now a national monument and landmark at Esplanade Park, the Victoria-styled Tan Kim Seng fountain was first installed at Fullerton Square in 1882 by the Municipal Commissioners to commemorate local Chinese merchant and philanthropist Tan Kim Seng’s (1805-1864) generous contributions to the construction of Singapore’s waterworks and MacRitchie Reservoir.

Specially built by Andrew Handyside & Co from England, the fountain towers at 7m tall and has decorations made up of classical figures. In 1925, it was relocated to Esplanade Park where it stood close to the coastline. Today, the fountain remains at the same position where it has been standing for the past 90 years, but the coastline has now shifted away from it due to the land reclamation.

Tan Kim Seng Fountain was given a massive restoration in 1994, where its water spout, lighting and pumping system replaced. Seven years later, it was gazetted as a national monument.

Gemmill Fountain (1864-Present)

Singapore’s first public drinking fountain, the Gemmill Fountain was donated by John Gemmill in 1864. An English auctioneer, banker and storekeeper, John Gemmill had lived in Singapore between the 1820s and mid-19th century, and later had Gemmill Lane named after him.

The Gemmill Fountain, made of marble with water spouting from the mouth of its carved lion head, is more of a drinking facility than a fountain. Its original location was unknown, but records show that it had been installed at Empress Place between 1939 and 1947, and Raffles Place in the early 20th century and the fifties. The fountain was damaged during the Second World War. It was later passed to the National Museum of Singapore in 1967. After a brief moment at the Heritage Conservation Centre, the fountain was returned to the museum with a fully restored and functional water spout.

Former Paya Lebar International Airport Fountain (1955-undetermined)

Tourists and visitors arriving at the former Paya Lebar International Airport would be greeted by an pyramid-shaped fountain that displayed the message “Welcome to Singapore”. Standing in the middle of a roundabout, the fountain was sponsored by Philips, which had established in Singapore in 1951, five years before the airport was opened.

In May 1955, the Paya Lebar International Airport became operationally ready. Costing a hefty $35 million in construction cost, the airport’s 2.4km-long runway was capable of handling the largest commercial aircraft then. The airport had served well for more than two decades until the late seventies, when it began to have difficulties coping with the increasing annual traffic in passengers.

A new arrival terminal was built in 1977, but just four years later, the airport’s civil aviation operations were officially ceased, replaced by the new international airport at Changi. The premises of the Paya Lebar International Airport was later taken over by the Republic of Singapore Air Force (RSAF).

Fountains at Town Centres (1970s-2000s)

Fountains were popularly used as part of the public amenities at the town centres of the new towns built in the seventies and eighties. The town centres of Ang Mo Kio, Toa Payoh and Clementi used to have large iconic fountains, where residents would sit leisurely around the fountains during the evenings and watch jets of water pumped into the air.

Over the years, however, the public interest waned as the fountains gradually fell into disrepair. The water dried up as the pumps stopped functioning, and loads of dry leaves started accumulating in the empty fountains, making them an unsightly feature in the neighbourhoods. By the late nineties and early 2000s, most fountains at the town centres were eventually dismantled and demolished.

Whampoa Dragon Fountain (1970s-Present)

Like a dragon well hidden in the middle of a heartland, the Whampoa fountain is perhaps not as famous as other iconic fountains in Singapore. Built in the seventies, one can only imagine how the oriental-inspired fountain looks like during its glorious days, when streams of water were constantly spouted from the mouth of the majestic dragon.

Today, the dragon cuts a sad figure as it is nothing more than a statue in the middle of an empty reservoir. But it remains an important and symbolic icon in the hearts of the Whampoa residents, who had strongly petitioned against the demolition of this defunct fountain during the late nineties.

Fountains at Roundabouts (1960s-1990s)

Like the town centres, roundabouts were once favourite venues for the construction of water fountains. Roundabouts, or circuses, were preferred at the junctions of major roads, before the traffic light system became widely used in the seventies.

Before the Holland Road Flyover was completed in 1996, there was a roundabout at the junction of Holland Road and Farrer Road. Named Farrer Circus, it had a fountain that was opened in June 1966 by then-Minister for Law and National Development E.W. Baker.

In the same year, another water fountain was unveiled at Tanglin Circus by former Minister for Culture and Social Affairs Othman bin Wok. Built by the Public Works Department (PWD) at a cost of $98,000, the fountain’s central jet of water was able to hit a height of 7.6m. At nights, the 50m-diameter fountain was illuminated with coloured lights that formed a perfect picture with the Hotel Malaysia (later Marco Polo Hotel) in its background.

The Tanglin Circus Fountain was the third fountain commissioned by the Singapore government, after the Farrer Circus Fountain and the crescent-shaped fountain in front of the National Theatre. It, however, only lasted a decade before its demolition in 1977.

Another famous roundabout, the Newton Circus, also had a fountain installed in 1970.

Iron-Cast Fountain at Raffles Hotel (late 19th Century-Present)

The 6m-tall cast-iron fountain currently standing at the Palm Garden of Raffles Hotel had a significant history. Originally made in Glasgow, Scotland, it was located at centre of the Telok Ayer Market (now Lau Pa Sat) in the late 19th century, where the iron structure of the market was also imported from Glasgow.

In 1902, the fountain was shifted to the Orchard Road Market, built in 1891. After the 80 years of operation, the market was closed and demolished in the seventies, and the iron fountain was kept and forgotten. It was not until 1989 when the fountain was rediscovered, and subsequent found a new home at the newly-restored Raffles Hotel.

The Raffles’ Statue and Fountain (1919-Present)

In 1919, the statue of Sir Stamford Raffles was set up at Empress Place, in front of the Victoria Memorial Hall, to commemorate the 100 years of founding of Singapore. Originally installed at the middle of the Padang in 1887, the bronze statue, at its new location, was decorated with a grand semi-circular colonnade and a marble-lined fountain pool.

During the Japanese Occupation, the Raffles statue was moved to the Syonan Museum (originally Raffles Museum, and today’s National Museum of Singapore). It was returned to its previous site at Empress Place after the war. The colonnade, however, was said to be missing or destroyed. The statue and fountain remain at the front of the Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall till today.

Published: 26 October 2014

Few will remember the Golden Palace Holiday Resort (金宫旅游胜地) today, but in the late sixties and early seventies, it was a popular leisure haunt for many Singaporeans, who would visit the place for food, drinks, music, parties, fishing, boating and picnics. The resort was located opposite the Tampines Army Camp at Jalan Ang Siang Kong, off Tampines Road 111/4 milestone. Today, the resort, army camp and the road had all vanished into history.

Before the construction of Tampines New Town in 1978, much of the old Tampines was a huge forested place with numerous Chinese and Malay villages, such as Teck Hock Village, Kampong Sungei Blukar, Kampong Beremban and Hun Yeang Village, scattered between Serangoon River and the now-defunct Loyang Road. The Golden Palace Resort stood out as a rare landmark at the largely undeveloped eastern side of Singapore.

Established in 1967 with a start-up capital of $2 million, a hefty amount in the sixties, the Golden Palace Resort occupied 20 acres (or 81,000 square metres) of land, roughly the size of 11 football fields. It came with many facilities, including an artificial pond with pavilions and connecting wooden bridges, two restaurants that served Chinese and European cuisine, a snack bar, a golden pagoda, a reception hall and a conference room. It also had nine chalets; half of them were regularly booked throughout the year.

Established in 1967 with a start-up capital of $2 million, a hefty amount in the sixties, the Golden Palace Resort occupied 20 acres (or 81,000 square metres) of land, roughly the size of 11 football fields. It came with many facilities, including an artificial pond with pavilions and connecting wooden bridges, two restaurants that served Chinese and European cuisine, a snack bar, a golden pagoda, a reception hall and a conference room. It also had nine chalets; half of them were regularly booked throughout the year.

One of Golden Palace’s star attractions was its Golden Pagoda Garden Nightclub; the management paid generously to invite foreign and local artistes in performing for the large crowds that filled up the seats during the weekends.

Despite being a big success in its 4-plus years of operation, the Golden Palace Holiday Resort, however, ran into issues by the early seventies. The company was embroiled in a saga that saw its six directors split into two factions. The deepening internal conflict meant that the management could no longer cooperate in running the business together.

In late 1971, it was decided that Golden Palace would be sold by auction. The asking price was rumoured to be $1.2 million, as the stakeholders looked to recoup some of their capitals. The auction, however, was aborted after the highest bid fell slightly short of the asking price. A provisional liquidator was then appointed by the Chief Justice to handle the daily business administration and management of the resort.

Even near its closure at the end of 1971, the resort and its facilities were still patronised by the public, demonstrating its vast popularity.

Two years later, after several unsuccessful bids by various interested parties, the resort was eventually bought over by the government for only $870,000. The Commissioner of Lands, acting according to the formal legal procedural requirements, completed the purchase on behalf of the President of the Republic of Singapore. The site of the former resort was subsequently leased to the Primary Production Department which made use of the existing pond for fish-breeding experiments.

Today, the only remnant of the once-popular yet short-lived Golden Palace Holiday Resort is the fishing pond located opposite the White Sands Shopping Centre and the Pasir Ris MRT Station.

An interesting trivia of Jalan Ang Siang Kong happened in June 1975 when a 3-foot black panther was spotted prowling near some chicken coops. It caused a big alarm among the residents, and armed policemen were dispatched to hunt the ferocious creature down. Both the Singapore Zoological Gardens and Singapore Pet Farm at Elias Road denied that the panther was an escapee from their premises. In the eighties, Jalan Ang Siang Kong was expunged due the construction of the Tampines Expressway (TPE), first between Elias Road and the Pan-Island Expressway (PIE), and later between Lorong Halus and Elias Road.

Published: 11 November 2014

Kusu, St John’s and Lazarus Islands belong to collective group known as the Southern Islands that is currently taken care by the Sentosa Development Corporation. The other islands under their charge are Sentosa, Pulau Seringat, Sisters’ Islands (Pulau Subar Laut and Pulau Subar Darat) and Pulau Tekukor (also known as Pulau Penyabong or Turtle Dove).

Other than private charters, there is only one ferry service, provided by the Singapore Island Cruise, to fetch the visitors from Marina South Pier to the Kusu and St John’s Islands.

Kusu Island

Located about 5.6km south-western of Singapore, Kusu Island is a small island with many variations in its name. Originally called Pulau Sakijang Pelepah, it is also known as Peak Island, Pulau Kusu, Pulau Tembakul, Goa Island as well as “Tortoise Island”.

Kusu Island’s Places of Worship

Records show that as early as the 1870s, Kusu Island was already famous in the region for its “holiness”. And pilgrims had been visiting the island at the start of the 19th century, even before the arrival of Sir Stamford Raffles.

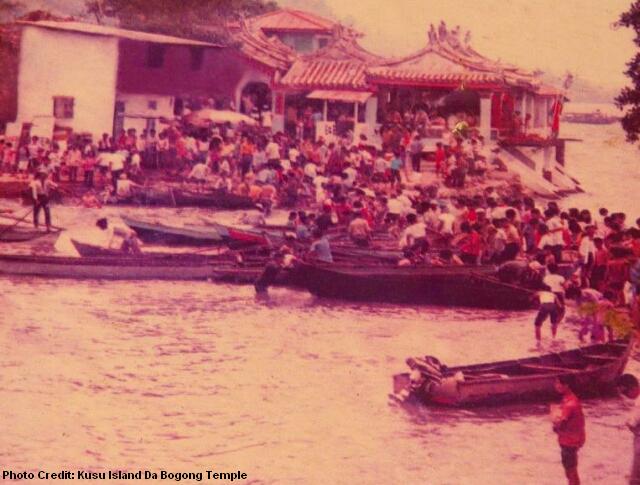

In 1923, a wealthy businessman called Chia Cheng Ho built a Taoist temple to dedicate to Tua Pek Kong (or Da Bogong 大伯公), also known as the God of Prosperity to the Chinese, and Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy. By the 1930s, in every ninth month of the Chinese calender, thousands of people would flock to the sacred island for their annual pilgrimage trips, taking sampans and motor boats from the congested Johnston’s Pier.

Arriving at the Tua Pek Kong Temple, the devotees quickly laid out their offerings of candles, joss sticks and money, fruits and “nasi kunyet“, a type of home-made yellow rice, for the gods. In return, they prayed for good health, wealth and safety. A yellow string, to be worn around the wrist, would be given by the shrine to the devotees as a preventive against accidents and evil spirits. Sometimes, flowers were purchased to be used for bathing, so that sins and misfortune can be washed away.

The Malay Kramats (holy shrines) were built at the top of a small hill in the early 20th century to commemorate a pious family – Dato Syed Abdul Rahman, his mother Nenek Ghalib and his sister Puteri Fatimah Shariffah. According to the tradition, a pilgrim had to climb 152 steps to reach the Kramats. It was said that if he could not complete the journey, he would be considered impure in his heart. Devotees would usually pray for five blessings, namely wealth, marriage, fertility, good health and harmony.

Outside the shrine, numerous stones were hanged on the trees and fences; they represented the vows by the devotees, which would be taken off each year after their pledges were fulfilled. Many devotees still practice this tradition today.

The Legends of Kusu

There were many fascinating legends about Kusu Island; one legend tells how a giant tortoise miraculously turned into an island to help a group of drowning fishermen.

Another one was the sworn brotherhood between a Chinese and Malay fisherman after their death. The Chinese fisherman had suffered a fit during a fishing trip and, after his death, was buried at the southern part of Kusu Island by his friends. A tombstone was erected in remembrance of dead fisherman, who was well-liked for his generosity and willingness to help others. The fishermen believed the dead spirit of their friend would continue to help them and other travellers out in the seas, looking after and protecting their safety.

As for the Malay Kramat shrine, the legend began when the Malay fisherman became the Kramat of Kusu after he was the first Malay to be buried on the island. One night, all the Malay and Chinese fishermen in the village had the same dream. In their dreams, the two dead fishermen who were buried on the island had become sworn brothers, and their relatives and friends were to visit Kusu once a year to pay respect.

Another legend, a lesser known one, was about the gods of the Tanjong Pagar hill who travelled across the waters to Kusu. Many years ago, the hill that stood opposite of the Tanjong Pagar Police Station had been slated for development. However, due to the difficulties faced during the leveling of the hill, it was decided that dynamites would be used to break up the hill. That night, five Arabs were spotted taking a sampan to Kusu.

Before arriving at the island, the passengers vanished, leaving the sampan man shocked and bewildered. The only explanation he could come up with was that the five passengers were the gods of the hill. The legend spread and was favourably received by the public, adding an even “holier” touch to Kusu.

“Grand Old Lady of Kusu Island”

A popular and famous temple caretaker used to live at Kusu Island for as long as 80 years. Ng Chai Hoong, also fondly known as “Bibi”, moved to Kusu from mainland Singapore in around 1870. The Tua Pek Kong Temple then was still a small ramshackle hut. She and her husband See Hong Yew took care of the matters in the temple until the mid of the 20th century.

Ng Chai Hoong passed away in 1950 at a ripe old age of 100. She was buried at the slope of the hillock opposite her home at Kusu. Years after her passing, devotees still visited her grave to pay homage.

Development of Kusu Island

In the 1960s, tens of thousands visited Kusu each year. Owners of the tongkangs, charging $2 per head for a two-way trip to the island, were reported to have earned a total of $25,000 in the month of pilgrimage. Hawkers selling food, joss sticks and candles also made their way to Kusu to enjoy a brisk business. With increasing crowds every year, the then-Marine Department in 1965 ruled that, for public safety, permits would be required for boats ferrying the people on pilgrimage trips to Kusu.

In September 1972, the Sentosa Development Corporation was established to oversee the development of Pulau Belakang Mati (today’s Sentosa) into a holiday resort. The statutory board was also tasked to manage other southern islands, including Kusu and Saint John’s Islands.

The 1.2-hectare Kusu Island was reclaimed and merged with another tiny coral island in 1975, a project undertaken by the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA), to become the current size of 8.5 hectares (about 12 football fields). The strip of sand that used to be under the waters during high tides, separating the Chinese temple and the Malay Kramats, was covered.

The 1.2-hectare Kusu Island was reclaimed and merged with another tiny coral island in 1975, a project undertaken by the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA), to become the current size of 8.5 hectares (about 12 football fields). The strip of sand that used to be under the waters during high tides, separating the Chinese temple and the Malay Kramats, was covered.

Ferry services were also started in the same year, taking visitors to Kusu from Clifford Pier and the former World Trade Centre Ferry Terminal. Amenities such as public toilets, lagoons and a hawker centre were built (vacated today except during the period of pilgrimage).

By the late 1970s, Kusu Island had become the second most popular island, after Sentosa, in the Southern Islands group. An estimated 235,000 visited the island in 1979, although a large portion of the visitors were pilgrims. The Sentosa Development Corporation was keen to attract more people to visit the island for picnics and enjoy its idyllic scenery by the lagoons.

St John’s Island

St John’s Island’s original name was Pulau Sekijang Bendera which means “Island of One Barking Deer and Flags”. The island had a significant history, where it was used as a quarantine station, detention centre and rehabilitation centre in the 100 years between 1870s and 1970s.

Famous Lazaretto

Records show that St John’s Island was designated as a quarantine station as early as the 1870s. In 1873, a cholera epidemic took away 357 lives in Singapore. A year later, Qing China suffered a serious plague outbreak. Due to the massive arrival of Chinese immigrants, a plague hospital was built at St John’s Island, and thorough inspections of ships coming to Singapore were carried out.

More than $300,000 were spent on the development of St John’s Island Quarantine Station since 1903, and as many as eight million people were inspected in the following twenty years.

In the early 20th century, St John Island also had its police station, located in front of the long jetty, with a Sikh force of one corporal and twenty men. Equipped with water tanks, pipelines, condensing house and rain water-retention facilities, the island was self-sufficient in the fresh water supplies. Staff quarters, steam boiler houses, storerooms and patient wards were built within the vicinity of the camp.

The oldest building on the island was the Superintendent’s sea-facing bungalow. It was constructed in 1894, at the time when China suffered the serious plague outbreak. The single-storey Tudor-styled bungalow is still standing today, although it is in a derelict state after being abandoned for many years.

By the 1920s, the quarantine station was one of the largest in the world, with sufficient accommodation for 6,000 people at the same time. Each year, the island’s two launches, named Hygeia and Crow, carried out disinfection of some 2,000 ships.

A Penal Settlement

St John’s Island was converted into a detention centre in the fifties, after the gradual slowdown of large-scaled immigration. As a detention centre, it housed many political prisoners and secret society members and leaders. After the mid-fifties, the facilities were converted into a rehabilitation centre for drug users and opium addicts.

Along with Kusu Island and other Southern Islands, St John’s Island was taken over by the Sentosa Development Corporation in the seventies. The drug rehabilitation centre was shut down in 1975, and over the years, the island was redeveloped into a resort that is popular with campers and students today.

Lazarus Island

Lazarus Island is located next to St John’s Island. The two islands are now linked together by a paved bund. Lazarus Island has a former name that was similar to St John’s Island’s. It was known as Pulau Sekijang Pelepah, which means “Island of One Barking Deer and Palms”.

The Island’s Past

There used to exist several convict prison confinement sheds on Lazarus Island in the late 19th century. The sheds were left abandoned after a prisoner, who was sentenced to life imprisonment on the island, made a successful escape. In 1902, a fire destroyed all the remaining sheds. The island was caught in another major fire in 1914, where almost all its vegetation was burnt down.

Like Kusu Island, Lazarus Island had numerous graves of those who had succumbed to various infectious diseases on the nearby St John’s Island. For a period of time, the island was forbidden ground to the public. Others were Muslim tombstones of the former villagers on the island. Today, the graves no longer exist as most of them had been exhumed in the late nineties.

In the sixties, Lazarus Island was used as a radar base fitted with a light-mast and high-frequency omni-directional range equipment for civil aviation. The equipment generated signals that could reach a distance of 200 miles, where they would be picked up by aircrafts coming into Singapore. The pilots could then accurately guide their planes along the selected tracks, thus ensuring the safety of all aircrafts. A Master Attendant used to be stationed on the island, taking care of the daily operational tasks.

The “Dollar” Islands

By the seventies, Lazarus Island, along with other Southern Islands, were taken over by the Sentosa Development Corporation. In 1976, some $11 million was spent on the land reclamation of Lazarus Island, Buran Darat and Pulau Renggit. Lazarus Island was earmarked for recreation development, with swimming lagoons, a family holiday camp, game courts, boatels and scuba-diving facilities proposed.

Pulau Renggit was also called Pulau Ringgit. In the early 20th century, some ninety Malay fishermen and a Chinese storekeeper had lived on the island. Their annual rent was a nominal dollar, which gave rise to the name of the island. Pulau Ringgit Kechil was another island forty yards away. Surrounded by a reef, it was a tiny coral isle with less than a dozen trees. Both were eventually absorbed as part of the enlarged Lazarus Island.

“Children of the Sea”

Lazarus Island had several Malay villages in the sixties and seventies. In 1963, the villagers welcomed former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew when he visited the island in his Southern Island Tour.

Lazarus Island had several Malay villages in the sixties and seventies. In 1963, the villagers welcomed former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew when he visited the island in his Southern Island Tour.

There was even a Pulau Sekijiang Pelepah Malay School, which created a sensational headline in 1970 when they won a host of trophies and smashed many records in the Radin Mas District Primary Schools swimming tournament.

Dubbed as “the Children of the Sea”, the participants were said to have trained in the rough waters around Lazarus Island for two months before the competition.

Development of the Island

By the eighties, Lazarus Island was almost emptied, with most islanders relocated to mainland Singapore. In 1988, the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (STPB) invited interested parties to submit proposals to develop Lazarus Island as a beach resort. The development plans, however, never materialised.

Published: 27 November 2014

Before the internet era, marketing of products was usually done through advertisements in physical forms, such as billboards, banners or posters put up at prominent locations with high human traffic. Large fonts, colourful themes, eye-catching logos and innovative slogans were commonly used to attract the public’s attention.

With the successful launch of Television Singapura in 1963, advertisements also found their way to a wider reach to the mass market through television broadcast. In 1964, the television station began selling airtime to the advertisers and sponsors for their TV programs. Other advertising means by the mass media included radios and cinemas.

By the eighties, public transport such as buses also started carrying advertisements of various brands and products.

Some old brands last till today, others rose and fell. There were some that left deep impressions to many Singaporeans, while the rest were easily forgotten. Here’s a look at some of the classic advertisement posters in Singapore in the past few decades:

Brand: Tiger

Advertising for: Bee

Slogan: It’s time for a Tiger

Year: 1933

“Drink more beer”. An advertising slogan like this will probably be disallowed today, but back in the 1930s, it was a catchy phrase to justify that beer was a nutritious and healthy thing to drink. Singapore’s first locally brew beer, Tiger Beer made its debut in 1932, produced by the Malayan Breweries Limited which later became the Asia Pacific Breweries (APB) in 1989. Today, Tiger Beer is sold in 60 countries worldwide.

Brand: General Electric

Advertising for: Refrigerator

Slogan: Nothing can be better than the best

Year: 1937

At prices more than $275, only the wealthy in Singapore would be able to afford this back in the 1930s. In fact, the refrigerator was so pricey that the advertising strategy was to convince its customers that the product from USA was a lifetime investment that one could not afford to take a chance with. And it came with a 4-year guarantee too. By then, General Electric was a reputable American brand with a significant history. It was established all the way back in the 1890s. In 1969, it invested a number of manufacturing plants in Singapore.

Brand: Tiger Balm

Advertising for: Pharmaceutical products

Year: 1947

Tiger Balm was developed in the 1870s in Burma but was developed into a business empire in the 1920s by Aw Boon Haw (1882-1954), the man who built Haw Par Villa, and his brother Aw Boon Par (1888-1944).

Aw Boon Har was a shrewd businessman and marketing genius. After he established himself in Singapore in 1926, he founded Sin Chew Jit Poh, a popular local Chinese newspaper that always carried the advertisements of his Tiger Balm products. At the openings of his Tiger Balm branches, he had his men dressed in tiger costumes. Aw Boon Har was also frequently seen in his iconic Tiger car on the streets, specially painted in orange with black stripes and fitted with a large metal tiger head.

Brand: CK Tang

Advertising for: Department store

Year: 1959

At a cost of $50,000, CK Tang Department Store was established at the junction of Orchard and Scott Roads in 1958, on a parcel of 1,350-square-metre land bought the legendary Tan Choon Keng (1901-2000). Although the department store faced the Chinese Tai San Ting Cemetery, its convenient location attracted many British housewives who lived at Tanglin. Its iconic green-tiled oriental-looking building was demolished in 1982, and was replaced by the new Tang Plaza.

Brand: Milo

Advertising for: Tonic food drink

Slogan: Replaces that energy

Year: 1959

An Australian product introduced in 1934, Milo, owned by Nestlé, was marketed as a tonic food, nutritious beverage and energy drink. It quickly gained worldwide popularity, especially in Singapore where it became a permanent fixture in the kopitiams. Several variations were developed over the years, such as Milo peng (ice Milo), Milo Dinosaur (a glass of ice Milo topped with extra Milo powder) and Milo Godzilla (a glass of ice Milo with ice-cream). In 1984, Milo was produced locally at the Jurong factory.

Brand: Lee Pineapple

Advertising for: Canned food

Year: 1959

From a small family-owned business started in the 1950s, Lee Pineapple is now a famous grower, canner and exporter of canned pineapple and juice to many countries in the world. Owning more than 10,000 acres of plantations in Malaysia, the Singapore company today produces 2.5 million cases of canned pineapple and juice each year, and employs more than 1,000 staffs.

Brand: Austin Seven/Mini

Advertising for: Automobile

Distributor: Borneo Motors

Year: 1960s

The popular Mini was first produced by the British Motor Corporation in 1959, and was sold worldwide under the brands of Austin Seven and Morris Mini-Minor. The Borneo Motors introduced Austin Seven into the Singapore market in the sixties, and marketed it as an economy car with a reliable engine and hydrolastic suspension.

Brand: Setron

Advertising for: Television set

Year: 1960s

With a combined start-up capital of $320,000, a group of businessmen set up the first television set manufacturing plant in Singapore in 1966. The factory, located at Leng Kee Road, began rolling out black and white TV sets. A year later, another Setron factory was opened at the new Tanglin Halt Industrial Estate.

By the seventies, the fast-growing local company had expanded into Malaysia, got listed in the Stock Exchange of Singapore, opened another seven-storey factory at Dundee Road, manufactured coloured TV sets and invested in the production of cassette recorders in a joint venture with Japanese electronic giant JVC. After a glorious decade, Setron eventually went into a decline in the early eighties.

Brand: Optima

Advertising for: Typewriter

Year: 1960s

German typewriter maker Optima was established as early as 1923. When its factory at Erfurt was destroyed during the Second World War, the company split into two, under the political circumstances that the country was divided into East and West Germany. The original factory was restored, while another factory was set up at Wilhelmshaven. The name Optima was retained by the eastern factory; the western one took up a new brand called Olympia.

The Optima E14, E stands for the Erika models, allowed typing of Arabic alphabet that was used in the Jawi script for the Malay language.

Brand: Baby Stork

Advertising for: Condensed milk

Year: 1960s

Cans of Baby Stork Condensed Milk were a familiar sight in Singapore provision shops in the sixties. It was manufactured by the Australian Dairy Produce Board using raw material from Australia worth some $2.2 million a year. The products were then distributed by the Malaysia Dairy Industrial Limited, established in Singapore in 1964.

Baby Stork faced stiff competitions against the Dutch Lady and Milkmaid in the sweetened condensed milk business. Dutch Lady was mass-manufactured in 1965 by Pacific Milk Industries (Malaya) Sdn Bhd, which changed its name to Dutch Baby Milk Industries (Malaya) Berhad in 1975, whereas Milkmaid was a popular product by Nestlé.

Brand: Ricoh

Advertising for: Camera

Year: 1960s

In 1936, Japanese entrepreneur Kiyoshi Ichimura founded Ricoh. The camera was marketed as one with precision workmanship, and equipped with high quality lens, clip-on exposure meter and duo-level focusing and built-in self timer. The prices, however, did not come cheap; each camera was sold for more than $200 in Singapore.

in 1960, Ricoh also came up with a range of auto-focus aim-and-shoot cameras at lower prices. Today, Ricoh is also a producer of printers, projectors and other office supplies.

Brand: Nestlé

Advertising for: Powdered milk

Year: 1966

Nestlé, a household brand in Singapore, had been operating its business in the country since 1912. Its wide range of food products, such as Milo, Maggi, Nescafé, Nespray, Kit Kat and others, remains a firm favourite among Singaporeans today.

Brand: Neptune

Advertising for: Restaurant

Year: 1970s

Ask any older generation of Singaporeans of their memories of Neptune, and most of them will tell you about the famous topless shows. In the eighties and nineties, Neptune was the only theatre-restaurant in Singapore to feature topless shows, until the arrival of the Crazy Horse cabaret in 2006. But Neptune was more than that. It was also a venue for concerts, wedding dinners, dance performances and even beauty pageants.

Managed by Mandarin Singapore, Neptune was established in 1972, competing against Tropicana in the local entertainment realm. By the mid-eighties, both Neptune and Tropicana experienced decline in their popularity due to a shift in public preferences. The famous Neptune dancers were disbanded in 1986, while Tropicana ceased their business three years later. Neptune held on until 2006, when it also closed for good.

Brand: Yeo Hiap Seng

Advertising for: Food and beverage products

Year: 1971

Yeo Hiap Seng was originally a small stall selling soya sauce by its founder Yeo Keng Lian. His sons Yeo Thian In and Yeo Thian Kiew moved to Singapore and established a shop of the same name at the junction of Havelock and Outram Roads. During the Second World War, Yeo Hiap Seng suffered considerable damages but was still able to produce soya sauce to sell to the market. By the fifties, it began to manufacture canned food for Singapore, Malaya, Borneo and Indonesia.

In the sixties, Yeo Hiap Seng added packet drinks and instant noodles to its diversified range of products. A family dispute in the nineties saw the company split up, and was subsequently taken over by property tycoon and one of Singapore’s richest men Ng Teng Fong.

Brand: Yaohan

Advertising for: Department store

Slogan: Yaohan grows with you

Year: 1974

Japanese retail giant Yaohan established its foothold in Singapore when it opened its first store at the newly-completed Plaza Singapura Shopping Centre in 1974. Popular among the Singaporeans, Yaohan specialised in providing one-stop shopping experiences and selling everything from fresh fish and meat to cosmetic and textiles. The household brand, however, ceased its operations in Singapore after its mother company declared bankruptcy in 1997.

Brand: National

Advertising for: One-push button rice cooker

Slogan: Just slightly ahead of our time

Year: 1975

Probably the first famous brand of Japanese electronics, National was founded in 1925 by Konosuke Matsushita. Its first products were battery-powered bicycle lights, but the brand was better known for its range of rice cookers and electric fans sold in the Asian markets in the seventies and eighties.

National had been under the parent company of Panasonic, which was formerly known as Matsushita Electric Industrial Co Ltd. Audio and video products bearing National Panasonic were once the favourites among the consumers. By the early 2000s, the National brand was gradually being phased out. It finally became officially defunct in October 2008.

Brand: Knife

Advertising for: Cooking oil

Year: 1976

The popular Knife brand cooking oil was manufactured by Lam Soon, a local company with a history that goes back to 1950, when local businessman Ng Keng Soon established his copra and canned food factory at Jalan Jurong Kechil. The Knife brand cooking oil became a household brand and was also sold in the Hong Kong market since 1963.

In 1970, Lam Soon ventured into palm oil sector and set up many plantations in East and Peninsula Malaysia. Over the years, Lam Soon’s business was diversified to soap, detergents, beauty care products, packet drinks and fruit juice.

Brand: Magnolia

Advertising for: Packet milk

Slogan: The long life milk with the fresh milk quality

Year: 1975

The brand of Magnolia was born in 1937. It owned a Singapore dairy Farm at Chestnut Drive in Bukit Timah by the 1940s, which had 180 acres of farmland and 800 imported cows. Magnolia’s classic pyramid packaging design was launched in the fifties, with a promotion slogan called “The Peak in quality in every household”.

Magnolia’s popular snack bars were opened in Singapore and Malaysia in the late sixties; the first being established at the old Capitol Building. In the following three decades, Magnolia expanded its business to include ice-cream, soya milk, packet drinks and desserts.

Brand: Yaohan

Advertising for: Department store

Year: 1977

After the success of its flagship store at Plaza Singapura, Yaohan expanded aggressively, opening numerous branches in Singapore. Yaohan Katong made its debut in 1977, followed by Yaohan at Thomson, Parkway Parade, Bukit Timah and Jurong in the next six years.

Brand: Plaza Singapura

Advertising for: Shopping mall

Year: 1978

One of the largest shopping centres in Singapore upon its completion in 1974, Plaza Singapura started with six levels filled with retail shops that sold a wide range of products. Yaohan was its anchor tenant until 1997 when the giant department store went bankrupt. Plaza Singapura underwent a major renovation in 2012 that cost more than $150 million.

Brand: Drinho

Advertising for: Packet drinks

Slogan: Drinho cools you down

Year: 1979

Also a product by Lam Soon, Drinho came in different flavours, such as soya bean, sugar cane, bandong, chrysanthemum and green tea. The brand is still going strong in the market today.

Brand: POSBank

Advertising for: Self-service banking facility

Slogan: Your national saving bank

Year: 1979

Singapore’s Post Office Savings Bank (POSB) was established as early as 1877. After the country’s independence, the bank was placed under the charge of the Ministry of Communications and, later, the Ministry of Finance. In 1976, POSBank received its 1 millionth depositor, and its total amount of deposit crossed $1 billion.

It launched its Cash-On-Line ATM Services in 1979; the early machines were set up at the POSBank branches at Robinson Road and Orchard Road’s Cold Storage Supermarket. One of its marketing strategies was to give out piggy banks in the model of the signature design of its ATM machines. POSBank was acquired by the Development Bank of Singapore Limited (DBS) in 1998.

Brand: Nestlé

Advertising for: Packet milk

Slogan: Today’s milk for today’s family

Year: 1979

Brand: Maggi

Advertising for: Chilli sauce

Year: 1980

When Maggi launched its chilli sauce in the early seventies, it creatively raised public awareness by referring the sauce to a grandmother’s recipe. Calling it the Grandma Test, they invited 50 grandmothers to taste the new chilli sauce. The result was, of course, positive. Soon, Maggi also introduced its sauce in tomato, chilli and garlic, and chilli and ginger flavours.

For decades, Maggi has been the favourite brand for chilli sauce and instant noodle for many Singaporeans. It is owned by Nestlé, whose R&D centre developed the popular “fast to cook, good to eat” Maggi Mee in 1979. In the mid-eighties, Maggi also launched another of its signature products. Named Maggi Cook-It-Right, the instant seasonings largely featured traditional local recipes in beef rendang, Nyonya stewed chicken and assam fish curry.

Brand: The Specialists’

Advertising for: Shopping centre

Year: 1982

One of the oldest shopping centres at Orchard Road, Specialists’ Shopping Centre was home to Hotel Phoenix Singapore and, more famously, the John Little departmental store. It was originally named Specialists due to the concentration of medical specialists in its early days, and it was built in the site of the Pavilion Theatre in the early seventies.

Owned by OCBC Bank, the 30-plus years old mall and hotel were finally demolished in 2008 to be replaced by Orchard Gateway, a new mall with restaurants, offices, hotel rooms and a library linked between two towers.

Brand: Jack’s Place

Advertising for: Restaurant

Slogan: The unchallenged steak house in town

Year: 1984

Jack’s Place was the first restaurant in Singapore to introduce affordable Western food. It had its roots in the sixties when Hainanese Say Lip Hai came to Singapore to work as a cookboy for the British army stationed at Sembawang. Mastering the techniques of cooking the best roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, Say Lip Hai started his own business in 1967, named Cola Restaurant and Bar to serve the British and Commonwealth troops and their families at Sembawang.

In 1968, Say Lip Hai had his big opportunity when his cooking was appreciated by a British housewife, who recommended him to start his caterings at her husband’s pub at Killiney Road. Her husband was called Jack Hunt. Say Lip Hai agreed if he was given the in-charge of the kitchen operation. When the British couple returned to England in 1974, they sold the business to Say Lip Hai.

One of Jack’s Place’s outlets is located at the Bras Basah Complex. Officially opened in April 1980, it is still going strong after more than 30 years.

Brand: Klim

Advertising for: Powered milk

Slogan: Klim is milk. Pure, creamy milk

Year: 1985

Spelt backwards of “milk”, klim was a Canadian product developed in the early 20th century to serve as a dehydrated powdered milk that could be kept for weeks without refrigeration. It made its way to Singapore in the 1920s, distributed by Getz Bros & Co. Klim was acquired by Nestlé in 1998.

Brand: Sara Lee

Advertising for: Snack Cakes

Slogan: Thank you Sara Lee

Year: 1985

Many Singaporeans would remember the catchy tune of “thank you Sara Lee” advertised on the TVs in the eighties. The butter and chocolate pound cakes, packed in their characteristic aluminum packaging, were the favourites for many locals. Sara Lee was actually an American brand established way back in 1949, when its founder Charles Lubin named his bakery business after her daughter.

Brand: Bata

Advertising for: Shoes

Slogan: First to Bata, then to school

Year: 1991

And finally we have Bata, the Czech shoe manufacturer which has just recently celebrated its 120th anniversary (and 83 years of establishment in Singapore). The first Bata store was opened in Singapore in 1931 at the Capitol Building along Stamford Road, and in 1964, Bata set up its factory at Telok Blangah. The BM2ooo (Badminton Master 2000), one of its signature products in the eighties and nineties, was a must-have shoes for every school boys and girls.

(Photo credits: National Archives of Singapore, Newspapers Archives of Singapore and Facebook Group “Nostalgic Singapore”)

Published: 12 December 2014

Over the years, the old Queenstown has seen its former buildings torn down one by one. Like the Forfar House (1959-1995), Queenstown/Queensway Cinema (1977-1999, demolished in 2013), Commonwealth Avenue Hawker Centre (1969-2011) and many others, the latest building to go is the former Queenstown Driving Test Centre, located between Commonwealth Avenue and Dundee Road. Its 10,500-square-meter site, roughly the size of two football fields, is to be redeveloped with new condominiums.

Singapore’s Second Driving Test Centre

Built in 1968 at a cost of $285,000, the Queenstown Driving Test Centre was Singapore’s second driving test centre after the one at Maxwell Road. Design with a state-of-the-art concept, the driving centre allowed 14 driving instructors to conduct as many as 300 tests in driving proficiency and Highway Code in a day. This was able to take some pressure off the Maxwell Road Driving Test Centre, which was facing increasing traffic congestion along Maxwell Road by the sixties.

In early 1969, the Queenstown Driving Test Centre was officially opened by Yong Nyuk Lin, the former Minister for Communications. An interesting trivia about the former driving centre was its driving test method. For the theory portion, the candidate would have to “drive” a miniature toy car on a model designed with traffic lights, pedestrian crossings and road markings. The tester would then ask the candidate questions in order to check his or her responses to different traffic conditions.

Beside conducting driving tests, the Queenstown Driving Centre in the early seventies also functioned as a centre for renewal of road taxes and driving licenses for all classes of vehicles. In 1973, the Public Service Vehicles Training School was held at the driving centre, providing refresher courses for bus drivers and conductors on traffic rules, road courtesy, and responsibility, conduct and attitude towards passengers.

In January 1974, the Registry of Vehicles passed a new ruling, stating that learner-drivers and motorcyclists must pass their Highway Code before they could be granted provisional licenses. This caused a surge in the number of applicants. The Queenstown Driving Test Centre, by 1976, was facing the same issue as what the Maxwell Road Driving Centre faced in the sixties. As the number of candidates applying for provisional driving licenses increased, the waiting period for its driving tests was stretched to five to six months, compared to the three months’ waiting period at Maxwell Road Driving Centre.

Due to the increasing demands, two additional levels were added to the Queenstown Driving Centre in 1975. The upgrading project was undertaken by the Public Works Department (PWD), allowing the floor space of the building to increase from 431 to 1,295 square meters. The ground level was converted into a waiting area, a collection centre and offices for the chief tester and cashier, while the second floor was mostly made up of classrooms.

Other Driving Test Centres

In May 1977, in order to decentralise testing centres in Singapore, a driving centre was established at Jurong, the first of such driving centres to be set up in an outlying area. The new driving centre rented its premises from the Jurong Town Corporation (JTC) and hired experienced testers from the Maxwell Road and Queenstown driving centres. Learner drivers took their tests conducted around Jalan Ahmad Ibrahim, Jalan Boon Lay, Boon Lay Way and Yuan Ching Road.

A year later, two more driving centres were opened as part of the Registry of Vehicles’ decentralisation plan; the Kampong Ubi Driving Test Centre was set up at Block 26 Eunos Crescent, and the other driving centre was located at Block 7 Toa Payoh Lorong 8.

In September 1985, the Singapore Safety Driving Centre was opened at Ang Mo Kio Street 62. The new driving centre came with a modern driving test circuit and facilities that simulated realistic road conditions for the learner drivers. Another similar driving centre was built at Bukit Batok in 1989 at a cost of $9 million.

Conversion into a Police Centre

In 1995, after 28 years of services, the former Queenstown Driving Test Centre was shut down. Its premises were occupied by the Queenstown Neighbourhood Police Centre between 1997 and 2005. Although the building was later leased to private colleges until 2011, many of its rooms still retained the signature Dacron blue colour of the Singapore Police Force.

Like the Queenstown Driving Test Centre, the Maxwell Road Driving Test Centre was taken over by the Traffic Police in 1978, with its Accident Branch relocated from the Sepoy Lines.

Published: 26 December 2014

The Last Kampong on Mainland Singapore

Lorong Buangkok was originally a swampy area. In 1956, a traditional Chinese medicine seller named Sng Teow Koon bought a piece of land at Lorong Buangkok and rented it to several Chinese and Malay families, which gradually formed a kampong over the years.

The closely-knitted kampong went through the racial riots of the sixties. Both the Chinese and Malay residents agreed to look after one another during the turbulent periods and keep the village unaffected by the external chaos. When the peaceful time returned, the village was actively engaged in gotong royong, helping each other in the construction and repairs of houses.

Today, the piece of land that Kampong Lorong Buangkok is standing on, about the size of three football fields, is owned by Sng Mui Hong, the daughter of Sng Teow Koon. Around 28 families are still living in this rustic village, paying tokens as monthly rentals to the landlord. There is also a kampong head, who takes care of the surau, daily prayers and other Muslim affairs within the village.

Flood-Prone Area

Lorong Buangkok has been a low-lying area that is prone to flooding during thunderstorms. So much so that Kampong Lorong Buangkok was once also known as Kampong Selak Kain, which means “lifting up one’s sarong” in Malay, as the residents had to lift up their sarongs to their knee levels in order to walk through the waters during the flooding.

In 1976, the kampong was hit hard by a downpour that lasted three hours. Some 40 Malay families were affected and had their Hari Raya preparation ruined as their beds, furniture and curtains were soiled by the flood water that covered the entire lorong.

History of Lorong Buangkok

Lorong Buangkok used to be part of the Punggol constituency, represented by Ng Kah Ting who served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Punggol for 28 years between 1963 and 1991.

In 1978, after several requests, the government approved a $770,000 project to metal 15 muddy trails at Lorong Buangkok and Cheng Lim Farmways. The upgrading took almost three years. By the early eighties, the residents of Punggol and Lorong Buangkok finally had new tarmac roads flanked by brightly-lit street lamps.

The Cheng Lim Farmways was a network of roads between farms and plantations at the southern part of old Punggol (where Sengkang’s Anchorvale neighbourhood is today), linked by a small trail named Lorong Buangkok Kechil (kechil means “little” in Malay). Lorong Buangkok had its network of farmways too; there were Buangkok North Farmways 1 to 4 and Buangkok South Farmways 1 to 4.

On the eastern side of Lorong Buangkok were the Seletar East Farmways, which had been redeveloped into the Fernvale neighbourhood of Sengkang. To cross over to either side, the residents and farmers of Lorong Buangkok, Cheng Lim and Seletar East made use of a simple bridge that spanned across Sungei Tongkang, an extension of the main Sungei Punggol.

Sungei Tongkang – From Stream to Canal

For years, the sluggish and narrow Sungei Tongkang was the main cause of the numerous flooding at Kampong Lorong Buangkok. The stream tend to overflow during downpours. In 1979, the Ministry of Environment’s Drainage Division decided to widen and deepen Sungei Tongkang, and convert it into a canal at a cost of around $1.8 million. Works were also carried out at the upper and lower parts of the river to ensure the water flowed smoothly.

Despite the upgrading, the kampong still suffered from occasional floods. It was especially hit hard by one as recent as 2004.

All the farmways above-mentioned were expunged by the early nineties, with their vegetable, chicken and pig farms demolished. The clusters of villages scattered around Lorong Buangkok, Cheng Lim and Seletar were also gone, making way for the development of the Punggol and Sengkang New Towns in the late nineties.

The housing estates of Fernvale, Anchorvale and Buangkok Crescent were up and running between 2002 and 2004, surrounding Kampong Lorong Buangkok, the last village standing in the vicinity. A jogging track and park connector were constructed in the late 2000s along the canal that was previously Sungei Tongkang.

Development and Possible Demolition?

By the mid-2014, the vast forested area beside the kampong was bulldozed, confining the Kampong Lorong Buangkok to its remaining strip of vegetation sandwiched between the canal and the cleared land. The new parcel of land is likely to be reserved for an extension of the existing Buangkok Crescent housing estate.

As for the kampong, it is not sure how much longer it will be able to hang on. After withstanding the test of time for the past 60 years, the clock, for now, seems to be ticking fast on Kampong Lorong Buangkok’s eventual demolition as development is inching ever closer to the last village of Singapore.

Updated: 13 January 2015

The four blocks at Yung Kuang Road (Block 63-66) used to be the pride of Taman Jurong. Not only that, at 21 storeys, they were the tallest flats at Jurong when they were completed in the 1970s, the unique diamond shape formed by the four blocks (when viewed from the top) also gained them an iconic landmark status in the vicinity due to their easily recognisable appearance.

A New Industrial & Residential Estate